Hucksters sit and stand in the street to sell their wares near the market. (South East corner of Third, and Market Streets. Philadelphia. Thomas Birch, 1799. )1

Note: Much of this article is based on Candice Harrison’s excellent 2013 article “Free Trade and Huckster’s Rights,” published in The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Harrison’s article is where I first learned of the story of Philadelphia’s hucksters and their fight for legitimacy. If this story interests you, I highly recommend taking the time to read it.

In 1805, after in their own words “the unusual severity of the last winter, and the prevalence of disease in the latter part of the summer” a group of nineteen women submitted a petition to the “Select and Common Councils of Philadelphia,” the first page of which reads:2

To the Select and Common Councils of the City of Philadelphia;

The Petition and Memorial of the Subscribers, respectfully represents;

That your Petitioners, rendered helpless by the infirmities of age, – enfeebled by sickness – or oppressed by the cares of Widowhood – have, for some years past, endeavoured to gain a livelihood for themselves and their children by vending in the market place fruit, nuts, and other small articles, more in demand for the tables of the rich, than of those in the middle walks of life:

That your Petitioners were not led to this mode of living from choice, but, being incapable of hard labour, they have pursued it rather than encrease the burthen with which private and publick charity, are already so severely tasked by casting themselves and their families on the publick for support:

That by the small profits made on their sales, your Petitioners have been enabled to raise a slender subsistence; and some of them had accumulated small sums, upon which they hoped hereafter to draw, for those comforts which mitigate the sufferings of more advanced age and encreaseing infirmities but, what with the unusual severity of the last winter, and the prevalence of disease in the latter part of the summer, their all is now nearly exhausted: – they wait the approach of the coming season with fearful anxiety: – should it too prove severe, and they be cut off from their usual means of support by a continuance of the measures which have lately been taken against them, they can hope for nothing, under this double calamity, but must prepare to meet the extremest miseries of cold and of hunger, or as paupers, seek an asylum, contrary to their inclination and their feelings, in the poor house!

The women were a group of hucksters, small-scale, predominantly women retailers who worked in the reselling business, buying “fruit, nuts, and other small articles” to then resell at small profits. 3 4 5 These women were just one piece of 18th century Philadelphia’s urban population.6 But what did daily life look like for those living in these large (for the time) urban centers? What did urban poverty look like for 18th-century women?

Philadelphia’s Constable Returns of 1775 provide some insight into the city’s common population. Broken up by ward, they often included the name, gender, and occupation of all persons aged 16 and older who lived at an address (although the gender of children wasn’t specified).7 Carole Shammas (1983) conducted a statistical breakdown of the 1775 Returns of Chestnut Ward (one of Philadelphia’s wealthiest neighborhoods) and the east part of Mulberry Ward (significantly less wealthy). These two returns contain some of the most detailed gender and occupation breakdowns in the Returns. In her analysis, she found only ⅓ of the women who lived in Chestnut Ward were married to male heads of household. The other 2/3rds are made up of enslaved women, domestic servants, and daughters over the age of 15. In Mulberry Ward, the percentage of married women was about 50%. The difference here is explained by the much higher number of live-in domestic servants and enslaved women in affluent Chestnut Ward. Shammas estimated around 9-11% of women in 1775 Philadelphia were the heads of their own households, without a husband to rely on for income.8 9

It is hard to make definite conclusions on the income level of many of these working women. Tax records can provide us some clues, but since tax accountability was left to an individual assessor to determine, it was in no way free from gendered bias.10 Karin Wulf (1997) in her studies of the 1775 Constable Records and the 1763 and 1775 tax assessments found numerous women who were assessed as owing no taxes, though they owned taxable property. Gender seemed to be among the subjective factors assessors considered when determining “civic responsibility” to pay taxes, and different assessors reached different conclusions. Mary Pritchet, a huckster from Walnut Ward was assessed in 1767 by both the city and provincial tax assessors; the provincial tax assessor valued her at £2 with no taxable property, while the city assessor valued her at £8.11 Retailing, ranging from huckstering to shopkeeping, was the most common occupation listed for women heads-of-household in the 1775 Returns. And while not definitive, the fact that around 40% of women retailers were assessed as owning no property,12 does give us a hint as to their economic status.

But nothing provides more clues to the public’s perception of these working women and men than the crackdown against hucksters beginning in 1779.

Before and even after the American Revolution, huckstering could be a way to earn a subsistence and even a stable livelihood. In the 1780s and 90s Barthena and Ceaser Cranchell, a free Black couple, and Caesar a founding member of the Free African Society, were able to start as traveling hucksters and eventually open a permanent storefront.13 But they seem to have been among the few. Starting in 177914, the city of Philadelphia began its attempt to push hucksters out of the market, kicking off a debate that would last for at least 25 years.

The 1779 ordinance explains its purpose as to stop “the forestalling and regrating15 of Provisions in and near the City of Philadelphia [which] has produced great Inconveniences, and, if not restrained, is likely to bring great Distress upon the Inhabitants of said City and its vicinity.”16 Inflation ran rampant through the American colonies, and especially through Philadelphia, America’s largest city. British occupation had upset trade patterns, and the city faced an influx of migrants, many poor and disenfranchised themselves.17 Once the city government or “corporation”18 regained authority they attempted to seize control of not only market prices, but of the market’s reputation, using inflation as an excuse to crack down on a mixed-race group of poor, visible, and vocal women.

The first legislation passed in 1779 provided any person buying food or “victuals” in or on their way to the Market with the intent to resell them at higher prices would be tried as a forestaller or regrater. Allowances were made for hucksters, but they were restricted to making their purchases after 10 am “in order that the Inhabitants of the said City, needing food for the Use of themselves and their Families may be first supplied”. 19

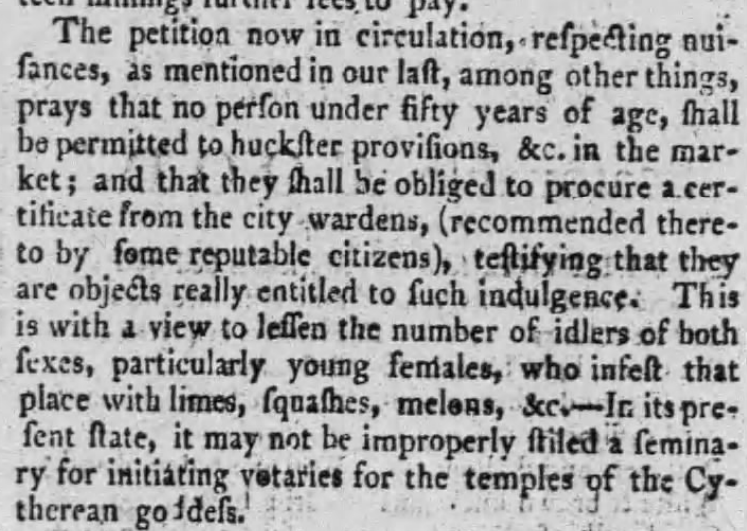

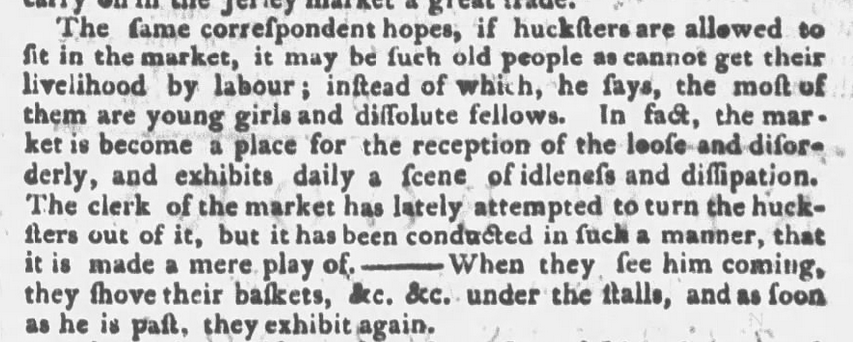

Following the act came rapidly increasing public vehemence towards hucksters who “infest the Jersey market.”20 21 Newspaper articles detail petitions circulated by the public calling for the city to institute stricter anti-huckstering laws. Proposed interventions ranged from laws restricting who was allowed to huckster: “no person under fifty years of age shall be permitted to huckster provisions,”22 introducing huckstering permits,23 and even “the total removal of them and other nuisances.”24 These petitioners were not subtle in who they wanted removed from the marketplace. “This is with a view to lessen the number of idlers of both sexes, particularly young females, who infest that place with limes, squashes, melons, etc. – In its present state, it may not be improperly stiled a seminary for initiating votaries for the temples of the Cytherean goddess.”25 The “correspondent” who called for huckstering to be limited to those over 50, explicitly places this proposed ideal huckster in opposition to “the most of [the hucksters] are young girls and dissolute fellows. In fact, the market is become a place for the reception of the loose and disorderly, and exhibits daily a scene of idleness and dissipation”. 26

Dunlap and Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser, August 16, 1785.

The Pennsylvania Journal, or, Weekly Advertiser, August 5, 1786.

The public outcry came to a head in June of 1789 when the city of Philadelphia significantly strengthened its laws against hucksters, citing “the great encrease of hucksters within the city for some years past, [which] has tended to enhance the prices of provisions and necessaries of life, has taken many able-bodied people from other more useful employments, and they have become an incumbrance and nuisance to the city at large, and especially to the said market.”27 Under this new law hucksters were barred from buying goods before 10 am not just in the market, but anywhere within city limits, from selling any goods bought from a “country person” on their way to market to sell the same, and from selling on any day except market days, and at any hours except market hours.

In response to this near ban, the hucksters fought back. A group of hucksters submitted a petition to the city of Philadelphia in 1791, which resulted in the introduction of the January 1792 “Huckster Bill” in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives. Debate stretched for months, but the hucksters were ultimately unsuccessful, and the city banned huckstering full-stop in December of 1792. 28

Resistance didn’t stop there. In 1795 Catherine de Willer was fined for practicing huckstering and appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, becoming the first huckster to do so but not the last. 29 None of the huckster’s bids proved successful until 1802, when their next petition to the newly appointed Democratic Republican government of Philadelphia resulted in a city ordinance that removed many of the restrictions on hucksters. Under this new ordinance, hucksters were free to vend any time they wanted, but goods had to be purchased outside of city limits.30 This success was short-lived, and public outcry against the hucksters increased again in response to their renewed presence in the marketplace. In 1805 Philadelphia elected another Federalist mayor, who took a hard anti-huckster stance. In October of 1805, he sent his constables on a spree of arrests, totaling twenty-two hucksters in just one day.31 This culminated in the final huckster’s petition written in December of 1805, in which nineteen women presented their vision of economic justice to the Select and Common Councils of Philadelphia.

What I find most interesting about the hucksters is not only did they resist the restrictions placed on them, but they showed deep political savvy and understanding, positioning themselves within large theoretical debates about the nature of the free market, who counts as the “deserving poor”, and what it means to be an American democracy.

In the debate around the 1792 “Huckster’s Bill,” the rhetoric focuses on the right of the corporation to regulate the market as they so choose, and the rights of vendors to have access to a free market. A January 17, 1792 Aurora General Advertiser article details the arguments made for and against the bill by the members of the House of Representatives. In defense of the corporation: “The market, [Mr. Fisher] contended, belonged to the corporation, and they had therefore a right to regulate it in such manner, as they conceived would tend to the public good. The corporation are the free choice of the citizens of Philadelphia, have a common interest with them, and therefore are best enabled to promote their welfare.”32 When they debate the right of the corporation to regulate the market, they do not mean the market in the theoretical sense, they mean the market as the physical structure. Here, at the beginning of the American economy, instead of debating the legitimacy and effects of this specific piece of legislation, the debate is over whether or not the city corporation has a right to regulate the market at all. And the defense of the corporation’s right to regulate is one that relies on the fundamental assumption of democracy itself – that the government chosen by the people, understands the best interests of the people they represent, and enacts legislation on their behalf.

It’s also interesting to note that in this, one of the first debates about the definition of the free market, the regulations are against the disenfranchised. From the same Aurora General article: “the bill before the committee, [Mr. Fisher] said, pointed at that clause of the ordinance, which was intended to suppress the practices of hucksters, buying early in the market to sell again, or buying up on the roads leading to the city, and disposing of the purchase at an enhanced price, to the great injury of the poor in the city.”33 Mr. Fisher seems to give no regard to the fact that the hucksters are the poor in the city.

Instead of causing “great injury to the poor in the city,” hucksters mostly served the middle class, wives responsible for the time-intensive work of maintaining their households but who weren’t wealthy enough to have an enslaved, indentured, or paid domestic servant who they could send to market in their place.34 For these middle-class women, door-to-door hucksters could have made all the difference in the management of their many laborious daily tasks. As the hucksters said themselves in their 1805 petition, “your Petitioners…[have] endeavoured to gain a livelihood for themselves and their children by vending in the market place fruit, nuts, and other small articles, more in demand for the tables of the rich, than of those in the middle walks of life.”35

Underlying Mr. Fisher’s argument in the House is another assumption. He sets the hucksters apart from “the poor in the city” because, in his mind and the minds of many others, the hucksters don’t fall into the category of the “deserving poor,” those the city should intervene to protect. Through a modern lens, hucksters are entrepreneurs, sourcing their own product, and filling a niche in the market. To many members of the 18th-century public, they’re “designing hucksters,”36 swindlers looking to lie and cheat their way to any profits they can. The plight of the hucksters in the 18th century is an example of the expectation creep that still preys on disenfranchised people today. In the case of the hucksters, the goalposts of what counts as the “deserving poor” keep shifting on them. The hucksters are working, most are not receiving public funds, and are not living in the almshouse. In fact, in their 1805 petition they specifically cite a desire to stay off the public dole “[should] they be cut off from their usual means of support by a continuance of the measures which have lately been taken against them, they can hope for nothing…but must prepare to meet the extremest miseries of cold and of hunger, or as paupers, seek an asylum, contrary to their inclination and their feelings, in the poor house!”37 But their work was not enough. “A Fellow Sufferer” wrote in to the newspaper in 1781 “This city pays the most grievous tax to all sorts of hucksters, particularly in the market. Let us view the market after ten or eleven o’clock, you will see it full of vegitables in the hucksters hands, of different ages, and for the most part young, which could earn their bread with their labour.”38 The argument boils down to these young women not working hard enough. “A Fellow Sufferer” finds an excuse to act against a group of young, visible women of multiple races for not working in a way they deem acceptable. 39They even go so far as to suggest the public would be better off if the hucksters were sent to the almshouse, writing “Would it not be great saving, if the city maintained ten or twelve old huckster women in the almshouse?”40 Anything to get these women off the streets.

In their 1805 petition, the hucksters take specific care to position themselves not only sympathetically, but to subvert the gendered stereotypes they’ve been saddled with for years. They exert their right to perform this work, and stress to the councilmen they are not conniving able-bodied young women, but weak, elderly, and unable to perform other laborious work.41 This group of women, largely unable to write,42 deeply understands the accusations against them, and sets out a case directly refuting those claims, while anchoring the argument in pathos. They note the ways those more advantaged than them are able to skirt restrictions, from selling directly from their cellars next to the market, to the large forestallers who journey out into the countryside to buy goods from farmers and sell at large scale in the market. And they end by asking the question: If the corporation is allowed to regulate against us, what would it look like to have them regulate for us?

The final paragraph of their petition asks the city to intervene on their behalf, to set aside dedicated stalls for hucksters in the market which hucksters could rent for a small fee.43

It would not become your Petitioners to direct the manner in which your benevolent intentions towards them might be accomplished: but they beg leave to suggest as a practicable mode of alleviating their distress, with the least possible infractions of the present system, that some particular and distinct stands, in or near the Market house, should by ordinance be assigned to them, for which they should individually pay a reasonable rent; – that from these stands all should be excluded except your Petitioners & those who like them labour under the infirmities of age or sickness, or are reduced by misfortune, and have families depending on them; – and that they should be limited to the sale of nuts, fruits and such other articles, the regrating of which may be deemed least disadvantageous to the buyer –

Such a plan, your Petitioners humbly apprehend might be adopted for their relief; and they trust that, if well considered, it will be found not at all disadvantageous to the Community, and not essentially to interfere with the present system of police in this behalf –”44

The petition was ultimately unsuccessful. Urban hucksters continued to face increasingly negative public perception as the 19th century wore on. 45 But their struggle reminds us that ideas we consider deeply philosophical were real in the Early American Republican, and had tangible impacts on people’s daily lives. The public was not removed from these conversations. In this instance, the debate was led from the street level up, with the hucksters wielding these ideas at their full power.

I’m resistant to frame this through a modern lens of triumph against incredibly strict and repressive gender roles. What remains to be learned is how exceptional the hucksters were. These debates happened in urban areas throughout the country, from New York46 to Baltimore.47 Is this a normal 18th-century story in which disenfranchised women exerted an amount of agency typically available to them? Does this indicate women in 18th-century America had more agency than we in the 21st century typically imagine them to have had? Or is it in fact a story of exceptional women fighting through strict barriers with the agency they could exert? Certainly the hucksters faced an incredibly gendered backlash, one that ultimately successfully enforced ideas of proper behavior within certain genders and classes. But to have made it as far down the path of political resistance as they did presumes a certain amount of foreknowledge and access. Like most things, the truth seems to lie somewhere in the middle.

- The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. “South East corner of Third, and Market Streets. Philadelphia.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. ↩︎

- “Huckster’s Petition to the Select and Common Councils of the City of Philadelphia, December 18, 1805,” Historical Society of Pennsylvania. ↩︎

- Candice L. Harrison. 2013. “Free Trade and Hucksters’ Rights!” Envisioning Economic Democracy in the Early Republic. The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 137 (2): 148. ↩︎

- Thomas Sheridan. 1796. A complete dictionary of the English language, both with regard to sound and meaning. W. Young, Mils & Son, Philadelphia. ↩︎

- Oxford English Dictionary. 2024. s.v. “huckster (n.), sense 1.a” ↩︎

- In contrast to our dense 21st century population patterns, at the time of the American Revolution less than 4% of the Colonial American population lived in cities, and Philadelphia was by far the largest. ( The Role of Cities in the American Revolution, Museum of the American Revolution). ↩︎

- Carole Shammas. 1983. The Female Social Structure of Philadelphia in 1775. The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 107(1): 70. ↩︎

- Shammas, 71-73 ↩︎

- This does not mean married women weren’t working and also earning income, see Karin Wulf’s chapter “Women’s Work in Colonial Philadelphia.” But as Shammas notes, the Constable Records did not indicate the occupation (or even the presence) of spouses of male household heads. Shammas was able to estimate the number of married women by assuming all male heads of households with children were married, assuming the number of widowers with children will balance out the number of married men without children (p. 71). See her article for her full methodology. ↩︎

- Karin Wulf. 1997. Assessing Gender: Taxation and the Evaluation of Economic Viability in Late Colonial Philadelphia. The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 121(3): 202. ↩︎

- Wulf, “Assessing Gender”, 212. ↩︎

- Shammas, “The Female Social Structure of Philadelphia in 1775,” 75. ↩︎

- Harrison, “‘Free Trade and Hucksters’ Rights,’” 152. ↩︎

- Pennsylvania Gazette, April 7, 1779; Pennsylvania Packet, April 8, 1779; Harrison, “‘Free Trade and Hucksters’ Rights,’” 155. ↩︎

- “Regrate: To buy up (commodities, esp. food) in order to resell at a profit in the same or a neighbouring market. ” Classified as historical and rare. (Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “regrate (v.1), sense 1,”) ↩︎

- Pennsylvania Gazette, April 7, 1779 ↩︎

- Harrison, “‘Free Trade and Hucksters’ Rights,’” 154-155. ↩︎

- “The corporation is composed of 15 Aldermen, chosen by the freeholders of the city, for seven years; 30 Common Councilmen, chosen by the freemen for three years, and of a Mayor, chosen by these two bodies from among the first” (Aurora General Advertiser, January 17, 1792 ) ↩︎

- Pennsylvania Gazette, April 7, 1779. ↩︎

- The Independent Gazetteer, August 13, 1785 ↩︎

- “The Jersey Market” was part of the market expansion, opened in 1764 for the use of sellers coming across the Delaware River from New Jersey. (Philadelphia Register of Historic Places, “Old City Historic District,” 2003) ↩︎

- Dunlap and Claypoole’s Daily Advertiser, August 16, 1785; Pennsylvania Packet, August 16, 1785 ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- The Philadelphia Journal or Weekly Advertiser, August 5, 1786; Harrison, “‘Free Trade and Hucksters’ Rights,’”, 155 ↩︎

- “the Cytherean Goddess” is another name for Aphrodite (Getty Museum, Cultural Objects Names Authority)

Dunlap and Claypoole’s Daily Advertiser, August 16, 1785; Pennsylvania Packet, August 16, 1785. ↩︎ - The Philadelphia Journal or Weekly Advertiser, August 5, 1786 ↩︎

- Dunlap and Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser, June 11, 1789; Philadelphia Gazette, June 17, 1789 ↩︎

- Harrison, “‘Free Trade and Hucksters’ Rights,’” 158 ↩︎

- Harrison, “‘Free Trade and Hucksters’ Rights,’” 160 ↩︎

- Harrison, “‘Free Trade and Hucksters’ Rights,’” 161-164 ↩︎

- Harrison, “‘Free Trade and Hucksters’ Rights,’” 165-169 ↩︎

- Aurora General Advertiser, January 17, 1792 ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Karin Wulf. 2003. Women’s Work in Colonial Philadelphia. In Major Problems in American Women’s History : Documents and Essays, 3rd ed, ed. Mary Beth Norton, and Ruth M. Alexander (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003), 102.

In this chapter Wulf does also suggest huckster women sold to other lower class women who lived on the outskirts of the city or whose labor or family commitments kept them from traveling into the market on market days. I would argue in this instance, while they might be selling goods to other people in poverty at a slight markup, it’s not predatory behavior but an earned upcharge for performing a service. Through my modern political lens, if the corporation wanted to prevent people in poverty from having to pay these small upcharges they could work to make the market more accessible. ↩︎ - “Huckster’s Petition, December 18, 1805,” Historical Society of Pennsylvania. ↩︎

- Dunlap and Claypoole’s Daily American Advertiser, October 16, 1779 ↩︎

- “Huckster’s Petition, December 18, 1805,” Historical Society of Pennsylvania. ↩︎

- Dunlap and Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser, September 22, 1781 ↩︎

- Harrison considers the increasing vehemence against the hucksters an effect of the rise of values of “republican motherhood” in the late 1790s to 1805, but the cultural idea that the respectable place for women is the private sphere predates the late 18th century. Through the revolutionary period it remained respectable for women to primarily socialize in private spaces. Ladies would host teas and salons within their homes. It was far more likely for men to convene in “third spaces” like coffeehouses and taverns. See Carole Shammas “The Female Social Structure of Philadelphia p. 78 for discussion of chaperoning and a story from Sarah Eve’s diary. Women were often told domestic work was labor more befitting to them, categories like laundress, domestic servant, seamstress, etc. See Karin Wulf’s chapter “Women’s Work in Colonial Philadelphia” for more detail about the categorization of women’s labor. ↩︎

- Dunlap and Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser, September 22, 1781. ↩︎

- Harrison, “‘Free Trade and Hucksters’ Rights,’” 170 ↩︎

- Only Mary Swarts is able to sign her name on the petition, the rest make their marks, and sign with an x. ↩︎

- Harrison, “‘Free Trade and Hucksters’ Rights,’” 171 ↩︎

- “Huckster’s Petition, December 18, 1805,” Historical Society of Pennsylvania. ↩︎

- Harrison, “‘Free Trade and Hucksters’ Rights,’” 173 ↩︎

- New York city passed a law in 1763 barring hucksters from purchasing in the market before 11 am. (Pennsylvania Gazette, September 8, 1763) ↩︎

- Harrison, “‘Free Trade and Hucksters’ Rights,’” 170 ↩︎

Leave a comment